Click to join the conversation with over 500,000 Pentecostal believers and scholars

Click to get our FREE MOBILE APP and stay connected

| PentecostalTheology.com

When my family moved to Bixby, Oklahoma in 1985, it was a tiny town of only 5,000 people and didn’t have a single fast food restaurant. Today it is over 20,000 people and it is hard to tell where Bixby ends and Tulsa begins. But in the early years, it was a small town on the stop from Muskogee to Tulsa along the Arkansas River. Originally, there were several ferries to cross the river, but in 1911, a bridge was built on what is today Riverside Street (between Memorial and Mingo). The Bixby bridge helped establish the town and unified the various surrounding area communities of Frye, Willow Creek, and Shellenbarger.

Bixby was a government township established in 1902. It was named after Tams Bixby, a member of the 1893 Dawes Commission. The first church in Bixby was a Missionary Baptist Church built in 1903 at the corner of Main and Breckenridge.

By 1915, the town had its first known Pentecostal community. The Bixby Bulletin reports that “the ministerial force of the ‘Holy Rollers’” were working on building a church building.[1] These Pentecostal believers (possibly Oneness) had a significant impact on Bixby. In April, they held a baptism service in the Arkansas River, and many were baptized.[2] During the summer, a prolonged campmeeting added many believers; fifteen of whom were baptized on the Arkansas River.[3] This was at a time when Bixby had less than 1,000 people.

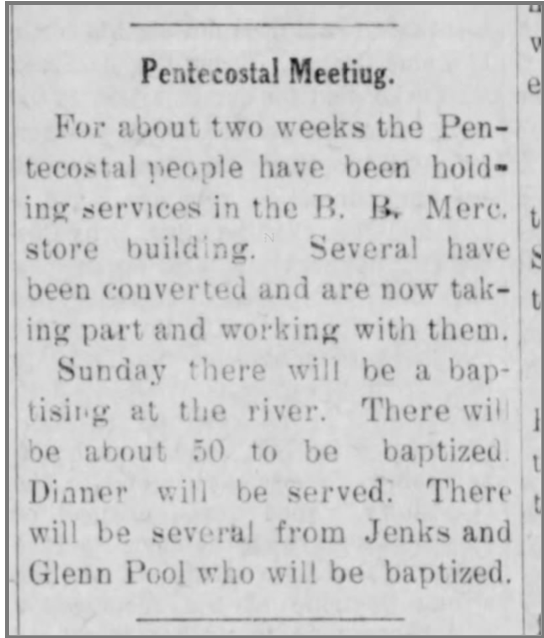

By early 1916, the Pentecostal Church began meeting in a storefront.[5] The new building saw many converts added to the church. By the end of the month, the congregation baptized fifty new believers in the Arkansas River.[6]

Beginning in 1920, the Assemblies of God was established in Bixby under the ministry of noted Oklahoma evangelist, Pearl Watts.[7]Assemblies of God Pastor, J. E. Chamless, led the church while teaming with Watts to also start a mission in Jenks.[8] Richard M. Phillips, co-editor of the Bixby Bulletin was important member of the church. He came to Bixby in 1908 to partner with W. W. Stuckey to publish the paper.[9] Phillips was a member of the church and was known for his sincere faith and Christian love. He often shared positive news about the Pentecostal group in the paper. Tragically, he died in a car accident in 1923.

Not everything related to the Bixby Pentecostal community was positive, particularly when related to the enthusiasm their worship services. F. E. Conrad opened a promising campmeeting in town on August 18, 1921, that quickly turned tragic. During a time of ecstatic praise, an attendee, Frank McCormick, fell on his one-year-old child. The church gathered to pray for the child, but the child died. The Tulsa World reported, news of the child’s death was “[s]preading over the town with uncanny swiftness [and] wrought the citizens to a fever heat. When a mob formed and was going to teach the Holy Rollers a lesson,” [10] three citizens, including Mayor, J. W. Stilts protected the group. Some left the town until things calmed down. More trouble arose for the church when E. B. Baker was charged with an “alleged disturbance” at the Holy Roller Church in April 1922. Though to trial, he was found not guilty.[11]

In May 1923, another Pentecostal mission was started in Bixby, and a revival was held on Breckenridge Avenue next to the telephone office.[12] The front page of the Bixby Bulletin, declared, “The sick are being prayed for and anointed with oil, and the Lord is healing.”[13] The church was a member of the Oneness denomination, Pentecostal Assemblies of the World. It was pastored by W. L. Schuessler, who held services every Saturday and Sunday night as well as a Thursday night prayer meeting. [14] Besides pastoring the congregation, he opened several businesses including a mattress company and the People’s Market on Dawes near the post office.[15]

The End of the KKK in Bixby

Part of the motivation of doing research on Tulsa and the surrounding communities was to understand what happed to Black Pentecostals during the Tulsa Race Massacre. One very interesting story I discovered was of when Greenwood residents came to Bixby. Since I could not tie it directly to Pentecostal churches in Bixby, this story didn’t make it in the book. But it is worth telling. The story comes from a 1974 booklet of anecdotal stories of Bixby’s history published by Citizen’s Security Bank put together by Burkett Wamsley called Ad Libs to Bixby History.

According to Wamsley, the Klu Klux Klan was once “Mr Big” in Bixby. For the most part, white Bixbians saw it as a social club and attended events to be part of the “society.” However, Bixby was not overly hostile to blacks, many of whom lived near by in the all-black community of Snake Creek near Leonard. Nevertheless, the KKK was a presence in Downtown in the Shaner Building built in 1917 (just east of Scott’s Hamburgers).

When the Tulsa Race Massacre started on streets of Greenwood early June 1st, 1921, most black Tulsans fled on the railroad tracks running north out of Tulsa. However, a few were able to flee south on the Midland Valley tracks that run from Tulsa, through Bixby and down to Muskogee. Wamsley describes the scene, “Hundreds of Negros, in various disarray of dress, flooded into Bixby. All night long they had fled south, driven by wild-eyed fear for their lives.”

Tired, hungry and fearful of meeting an equally hostile white community in Bixby, the refugees found quite the opposite. Earlier, some of Bixby’s citizens had jumped on the train to see what was taking place in Tulsa. After seeing the destruction and death, many returned with empathy in their hearts for the victims as “front doors flew open to their black visitors all over town. Food clothing, shelter, money. . . . plus transportation to Tulsa, or so some distant place was provided freely.”

The warm welcome and hospitality shown by Bixby’s white citizens effectively put and end to the KKK in Bixby. If treating fellow human beings this way was what the KKK stood for, Bixby would have no more of it. Says Whamsley, “The local membership has seen and heard enough that June 1, 1921 to resign totally and forever from the lodge.” There is no way to know if Pentecostals were among those who sheltered black Tulsans. But one would hope that the love of Jesus was a primary motivator to love their neighbors who arrived on their door steps.

This amazing story, told during the time when few in Tulsa were talking about it, included some of the famous photos from Greenwood’s destruction. The empathy of the Bixby citizens and the way they welcomed families into their homes shows the even in this era of white supremacy, this was not the case for everyone. As I drive the downtown streets of Tulsa today, I cannot do so without my mind’s eye thinking of that terrible day and how Bixby’s doors were wide open to those in need.

To read more about the story of Pentecost in Tulsa and the experiences of Black Pentecostals during the Massacre, see my book Pentecost in Tulsa.

[1] “Local Items,” Bixby Bulletin, January 8, 1915, 6. This mentions that they left a building half built, but apparently that was only temporary.

[2] “Jenks Items,” Bixby Bulletin, April 9, 1915, 3.

[3] “Local Items,” Bixby Bulletin, June 25, 1915, 6.

[4] “The Community,” Bixby Bulletin, March 31, 1916, 5. The list of churches included: The Christian Church, General Baptist, Missionary Baptist, M. E. Church, M. E. Church South, and Pentecostal Church.

[5] Bixby Bulletin, April 14, 1916, 1.

[6] “Pentecostal Meeting,” Bixby Bulletin, April 21, 1916, 3.

[7] “Revival,” Bixby Bulletin, February 6, 1920, 3.

[8] “Bixby and Jenks,” Pentecostal Revival, March 20, 1920, 14.

[9] “R. M. Phillips Killed in Auto Accident,” Bixby Bulletin, December 14, 1923, 1.

[10] “Dismisses Riot Charge,” Bixby Bulletin, September 23, 1921, 6; “Holy Rollers Cause Tragedy at Religious Meeting,” Tulsa Daily World, September 4, 1921, 1.

[11] “Local Items,” Bixby Bulletin, April 7, 1922, 5.

[12] “Pentecostal Mission,” Bixby Bulletin, June 8, 1923, 1.

[13] “Pentecostal Revival,” Bixby Bulletin, May 23, 1923, 1.

[14] It is likely that his was a white P.A.W. church. By 1923, some of the white members of the P.A.W. were breaking off to start all-white Oneness groups. However, there certainly were blacks living in the Bixby area, especially in the Snake Creek community between Bixby and Leonard, which was an all-black community.

[15] “Local Items,” Bixby Bulletin, July 18, 1924, 4. Schuessler moved in July 1924 to Albany, Texas.

Anonymous

Bixby, Oklahoma in 1985 was a tiny town of only 5,000 people and didn’t have a single fast food restaurant. Today it is over 20,000 people and it is hard to tell where Bixby ends and Tulsa begins. But in the early years, it was a small town on the stop from Muskogee to Tulsa along the Arkansas River. Originally, there were several ferries to cross the river, but in 1911, a bridge was built on what is today Riverside Street (between Memorial and Mingo). The Bixby bridge helped establish the town and unified the various surrounding area communities of Frye, Willow Creek, and Shellenbarger. Bixby was a government township established in 1902. It was named after Tams Bixby, a member of the 1893 Dawes Commission. The first church in Bixby was a Missionary Baptist Church built in 1903 at the corner of Main and Breckenridge. Perhaps Peter Vandever and Philip Williams can share similar stories about their families with @everyone in the group?

Anonymous

That was great, thanks for sharing, atlist I have a clue of your story, we thank God 🙏

Anonymous

Bishop Bernie L Wade our friend Larry Martin has argued against KKK and Parham, but the evidence is much there as well as with Selma White – you just cant call the white black… #noPunt intended here @all https://www.pentecostaltheology.com/charles-parham-racial-roots-of-the-pentecostal-movement/

Anonymous

Troy Day it’s sad to see such anachronistic judgments of Pentecostal leaders, who weren’t more racist than Episcopalians, Presbyterians, Catholics, Methodists, or Baptists of the same Jim Crow era. None of these churches had as much joint black and whites worshipping together as Pentecostals. Not even close! My father was often the only white man in some black churches, colored as they were called back then.

Anonymous

Philip Williams do you mean Pentecostalism is NOT moving in the plans of God?

Anonymous

Troy Day when led by the Spirit but not when led by science. Racism was based on science.

Anonymous

do share your revelation here with @everyone Ron Culbreth Ivan Karel surely Elving Ellis or Link Hudson Ricky Grimsley will have a non-southern response to this

Anonymous

Most activist today would say that if you participate with the rules you are consenting. However, in consideration of the law back then, people were afraid to break it. Charles Parham  continued to follow segregation laws, and some would say it was consent but I would say it was fear of arrest. I’m glad that there are those who resisted such nonsense, such as Seymour and the congregants that followed after him. Because of early Pentecostals Segregation is now a defeated foe.

Anonymous

Elving Ellis says WHO? it is absolutely NOT true Charles Parham  continued to follow segregation laws Bishop Bernie L Wade Bishop Gerishon Njoroge

Anonymous

Troy Day if he stopped following segregation laws, then that’s great.  I’m not going to make an argument out of it because I didn’t know that.  I just remember reading about how Seymour had to sit outside and watch the services through the doors.

Anonymous

Elving Ellis Though Seymour’s attendance at Parham’s school violated Texas Jim Crow laws, with Parham’s permission, Seymour simply took a seat just outside the classroom door. Bishop Bernie L Wade It is generally accepted that Seymour was positioned outside the classroom on the veranda and had to learn ‘at a distance.’

Parham had been preaching foundational Pentecostal doctrine (or the ‘apostolic faith,’ as he called it) for some years and had first-hand experience of Holy Spirit baptism with the sign of tongues. The first occasion was at his Bible School in Topeka, Kansas on January 1st 1901 and in 1903 he was part of an outbreak of revival, which included Pentecostal baptism and divine healing, at Galena, Kansas. Subsequently he began a string of churches, mostly around the suburbs of Houston, Texas, where he also began another college to train missionary evangelists.

It was here at Houston that William J. Seymour, became convinced that Parham’s teaching on the baptism of the Holy Spirit, with the initial evidence of tongues, was soundly Biblical and added it to his well established Wesleyan-Holiness theological system.

Anonymous

Pentecostal leaders as eminent as Aimee Semple McPherson who,

from her earliest days of ministry insisted upon holding meetings among Southern

blacks, also spoke at a number of Ku Klux Klan meetings.8

Charles F. Parham

was singing the praises of the Klan as late as 1927.9

To be sure, in spite of public

pronouncements by some Pentecostal leaders against membership in the Klan, I

have been told within the past five years by at least one national leader in a

Pentecostal denomination that there continue to be some Pentecostals in his

denomination who are regular members of the Klan.10 https://www.pentecostaltheology.com/charles-parham-racial-roots-of-the-pentecostal-movement/

Anonymous

Christianizing the Klan: Alma White, Branford. Clarke, and the Art of Religious Intolerance. Lynn S. Neal. According to the biblical book of Daniel

ALMA WHITE, PILLAR FIRE BISHOP, GIVES ADDRESS ON K. K. K. SUBJECT. Preceding Bishop White’s address, ten masked members of the Klan entered the auditorium

https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=TDT19250120-01.2.12&e=——-en-20–1–img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA——–0——

MacRobert and Mickey Crews claimed that whites in the Church of God ranged from giving no resistance to separation to being “more than happy” with it,2 and David Edwin Harrell said the story of blacks “followed the same path of segregation”3 as other denominations, the evidence leads to more complicated conclusions. Howard Nelson Kenyon, citing the institu- tion of the church as the “only opportunity for black-led initiative” in the South, attempted an explanation that corresponds with our knowledge of the time and place, but his use of writers from a later time to explain the thinking in the first twenty years of the church oversimplified the reality of what was occurring in the Church of God at that time.4 The circumstances preceding this partial split went beyond the ubiquitous, systemic racism of the times, and it is an oversimplification to treat this split as analogous to the experiences of other Pentecostal denominations at that time. Serious conflicts within the Church of God in the years leading up to 1922 may shed more light on the partial split than purely racial considerations.

Anonymous

BE VERY careful what you post in this OP Bishop Bernie L Wade FB may restrict your account for posting the TRUTH on how early white Pentecostalism was infiltrated by the klan … Isara Mo William DeArteaga J. Stephen Conn Michael Ellis Carter Jr.

Anonymous

Troy Day noted

Anonymous

Bishop Bernie L Wade but NO proof presented from you just yet 😉